1

1 1

1

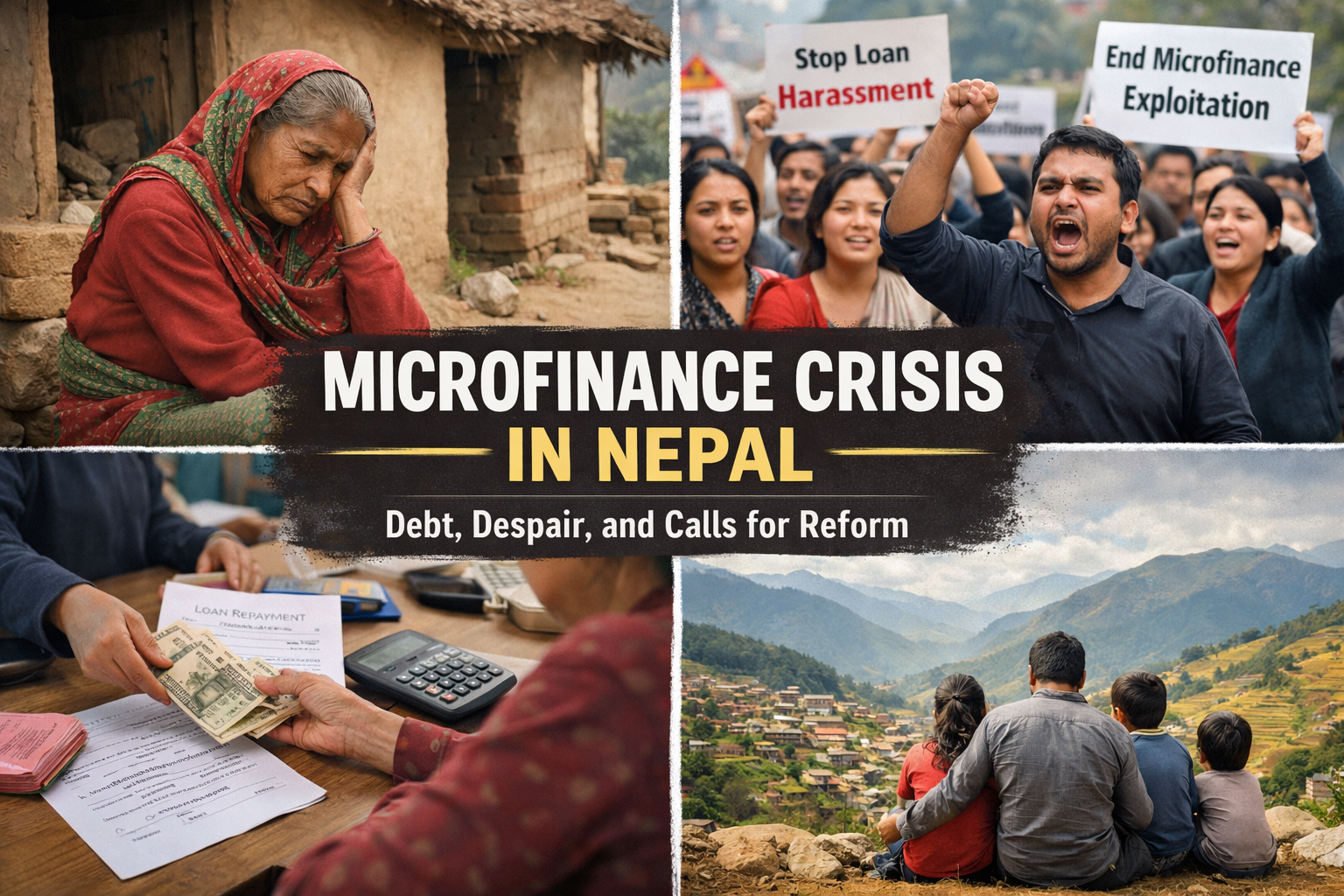

An in‑depth investigation into the rise of microfinance, mounting borrower hardship, protests, and the path ahead

By Nepali SMM Media.

Kathmandu, Nepal — Over the past two decades, microfinance institutions (MFIs) have become fixtures in Nepal’s financial landscape. Designed to expand credit access to underserved rural and low‑income populations, these institutions now boast millions of customers across the country. Yet, in recent years, mounting complaints, protests, and government interventions have exposed deep fractures in the sector — revealing how a tool once hailed for empowering the poor has sometimes contributed to economic distress.

This detailed investigation explores how microfinance developed in Nepal, the criticisms levied against MFIs, the human stories behind debt disputes, regulatory responses, and what reforms might stabilize the sector for borrowers and lenders alike.

Microfinance in Nepal traces its roots to the late 20th century, inspired by global movements to promote financial inclusion. The idea was simple: provide collateral‑free loans to individuals — especially women, farmers, and small entrepreneurs — who lack access to traditional banking services.

Over time, what began as niche community‑oriented lending expanded dramatically. Licensed microfinance institutions now operate under the supervision of the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), and according to NRB data, there are nearly 60 licensed microfinance institutions serving millions of borrowers across the country.

This expansion seemed promising: for many Nepalese households, especially in rural districts, MFIs offered the only feasible route to capital for farming, small trade, or education — sectors often overlooked by commercial banks requiring collateral and stringent documentation.

Despite their original mission, MFIs increasingly faced criticism from borrowers and advocacy groups. In numerous media reports, debtors have accused microfinance lenders of exorbitant interest rates, aggressive collection tactics, and financial pressure that strained household stability.

One recurring complaint has been the perception of high cost of credit. Although NRB directives cap the interest rate at around 15 percent per year (plus limited service charges), many borrowers — especially those with multiple overlapping loans — report that repayments grow much larger than expected. Economists point out that while MFIs are required to follow regulatory caps, service charges, insurance, and other fees can make the effective cost of borrowing significantly higher.

Compounding this issue is the widespread practice of multiple borrowing, where individuals take loans from several institutions simultaneously to repay existing debts or meet ongoing expenses. An NRB committee report revealed that over 400,000 borrowers had taken loans from two or more MFIs, representing a significant portion of microfinance debt — a figure experts warn can lead to spiraling liabilities for individuals and families.

This dual liability — high lending cost and multi‑institution borrowing — has strained borrower finances, particularly when businesses or income‑generating activities fall short of expectations due to economic shocks, pandemics, or seasonal instability.

Although systematic data linking microfinance loans directly to extreme outcomes like suicide is not established in official records, several personal stories reported in credible outlets and wider public discourse illustrate the intense human stress associated with debt.

In Rautahat, for example, Dil Kumari Karki — a small trader — described how her debt burden ballooned from an initial modest loan into a much larger obligation over four years. She attributed this expansion to high effective costs and overlapping obligations.

Independent reports beyond mainstream media have also shared distressing accounts of borrowers selling assets or struggling to meet repayment demands from lenders. While some narratives emerge primarily in social commentaries or local platforms, they highlight the emotional and financial pressure that families face under debt loads that consistently outpace their income.

Importantly, scholars and consumer advocates caution that individual outcomes vary — not all distress can be attributed solely to microfinance. Broader economic factors like employment scarcity, markets failing to absorb goods, and external shocks (e.g., COVID‑19) play crucial roles. Yet the perception of pressure and financial risk among borrowers is palpable and widespread.

Visual protests in major cities have brought borrower concerns into public view. In Kathmandu earlier this year, groups of microfinance borrowers from various districts marched to demand systemic changes — including loan write‑offs, removal from debt blacklists, and release of collateral seized for unpaid obligations.

In some districts like Mahottari, protests resumed even after government agreements, as borrowers claimed that MFIs had not fully complied with terms agreed upon earlier — including halting aggressive recoveries and respecting relief measures.

These protests underscore the social frustration that many feel with the status quo — a sector meant to empower low‑income residents now seen by some as a source of stress that deepens financial vulnerability.

Faced with rising tensions and borrower grievances, the government of Nepal and the Nepal Rastra Bank have taken notable steps.

In March 2024, the government signed a six‑point agreement with a committee representing aggrieved microfinance borrowers. Key elements included stricter enforcement of maximum allowed interest and service charges, limits on lending to individuals with existing high debt loads, and measures to prevent borrowers from taking more than one loan concurrently from multiple institutions — a central complaint linked to over‑indebtedness.

The agreement also charged authorities with ensuring financial literacy for borrowers before issuing loans and mandated action against MFIs that violate NRB directives, particularly in loan restructuring and rescheduling.

Furthermore, the government formed a taskforce comprising experts, central bank officials, and borrower representatives to study the microfinance sector’s systemic challenges and recommend reforms. Among recommendations from this taskforce was the suggestion to mandate insurance coverage for projects funded by microfinance loans — a measure aimed at protecting borrowers from total loss if their businesses fail.

The central bank itself has also tightened oversight. Since early 2023, it introduced amendments to unified directives on MFIs — including restrictions on lending to individuals who already hold loans from other banks or financial institutions, a measure intended to curb multiple borrowings.

Understanding why microfinance debt has become an issue requires looking beyond MFIs themselves to larger economic trends in Nepal. Decades‑long structural challenges — including limited industrial growth, reliance on remittances, and rural unemployment — mean that many borrowers lack steady revenue streams to repay loans even under favorable terms.

The COVID‑19 pandemic and global economic slump hit small businesses and informal sector workers hard, reducing incomes just as many were expected to make loan payments. International surveys have shown that micro, small, and medium enterprises globally faced threats to survival during the pandemic, and Nepal likely mirrored these pressures.

Additionally, borrowers often lack comprehensive financial literacy or formal credit histories, leading to decisions that overestimate their capacity to repay — a problem both borrowers and lenders acknowledge.

Economists and development professionals stress that microfinance as an instrument remains vital for financial inclusion — particularly for populations excluded from traditional banking. Yet many argue that oversight, risk assessment, and borrower education must improve.

Research has highlighted that group lending models, widely used by MFIs, can create social pressure to repay that borders on public humiliation if payments are missed — a dynamic that can exacerbate stress among vulnerable communities.

Experts underscore that the core value of microfinance lies in responsible lending — matching loan size and repayment structure to realistic income expectations — rather than maximizing institutional profits at the expense of borrower stability.

The future of microfinance in Nepal hinges on a balanced regulatory environment that protects borrowers without strangling financial institutions that serve vital needs.

Key reforms being discussed include:

Enhanced financial literacy programs for borrowers prior to loan agreements

Stronger enforcement of interest and service charge caps

Unified credit information systems to prevent over‑borrowing

Safety nets such as insurance for funded projects

Clear grievance mechanisms for borrowers to report unfair practices

These reforms could help ensure that microfinance fulfils its original mission — enabling economic participation and entrepreneurship — rather than entangling families in cycles of debt due to asymmetric information or misaligned incentives.

Microfinance in Nepal stands at a critical juncture. For millions of borrowers, MFIs have provided access to finance that was previously unattainable. Yet for a significant number of households, the burden of repayment, overlapping debts, and perceived high cost of credit has led to genuine economic hardship and heightened public scrutiny.

Government efforts, regulatory tightening, protest movements, and ongoing policy discussions all point to a sector in need of recalibration — one that must balance access to credit with protections against undue financial stress.

The stories of borrowers’ struggles, the government’s interventions, and the sector’s broader challenges reveal an urgent need for a more inclusive, transparent, and sustainable model of microfinance — one that protects the dignity and resilience of Nepal’s most vulnerable citizens while supporting responsible economic growth.