1

1 1

1

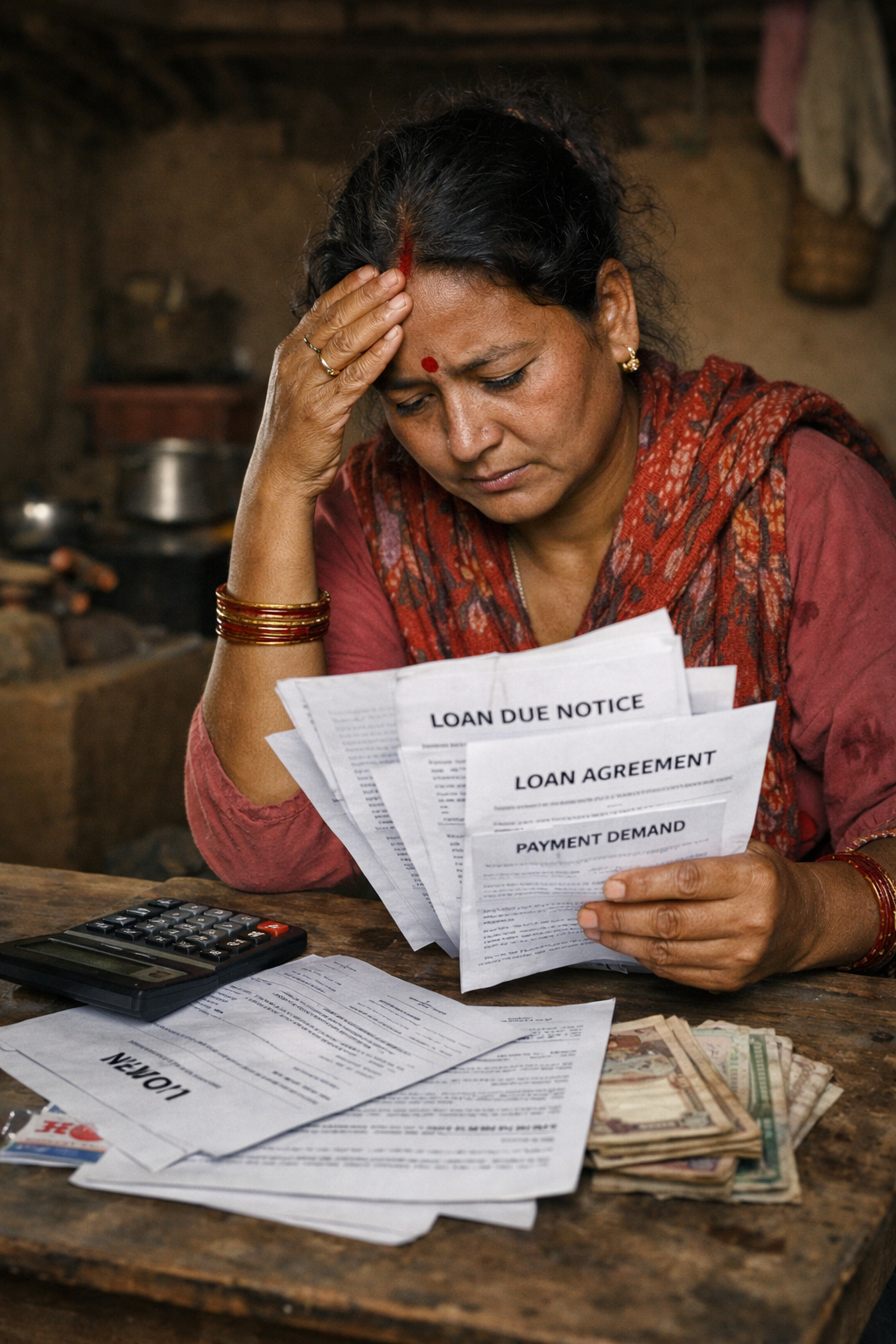

Microfinance was once heralded as a powerful tool to alleviate poverty, empower women, and bring financial services to the underserved communities of Nepal’s rural hills and Terai plains. But today, for many Nepalese families, microfinance has become a source of unending debt, emotional distress, and social turmoil. Despite its stated mission to uplift the poor, the reality for thousands has become starkly different: a lifetime trapped in loan cycles with little material benefit.

Microfinance in Nepal grew rapidly over the past two decades, with dozens of institutions lending billions of rupees to low-income households. These loans were designed to help start small businesses, buy livestock, or support consumption needs. But as the sector expanded, it became more profit-oriented and less focused on sustainable development.

Instead of helping the poor climb out of poverty, many microfinance borrowers now find themselves piled under multiple loans and skyrocketing interest costs. Research and media reports have found that borrowers often accumulate debts from two or more microfinance institutions, creating a situation where they borrow new loans simply to repay old ones.

In some extreme cases documented by Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), individuals had taken loans from over 20 different MFIs simultaneously — a clear indicator of over-indebtedness and flawed lending practices.

Although Nepal’s central bank capped microfinance interest rates at 15–16.5 percent per year, many borrowers report being charged much higher effective rates due to service fees, penalties, and aggressive collection practices. These combined costs can consume a large portion of household income, making it extremely difficult for borrowers to repay the principal.

This environment creates a vicious cycle of debt:

Borrowers miss payments due to high costs.

They take new loans to cover old debts.

Interest compounds across loans.

Stress, social pressure, and penalties increase.

This cycle often continues until borrowers are forced to sell assets such as land or livestock to keep up, leaving families financially and emotionally devastated.

One of the most troubling issues is loan stacking — borrowing from multiple MFIs simultaneously to pay off earlier loans. This practice became widespread because there was no integrated credit information system linking all lenders. As a result, borrowers could easily take multiple loans without thorough checks on their repayment capacity.

In response, the Nepal Rastra Bank introduced policies limiting how many MFIs a person can borrow from. However, the damage had already been done in many rural communities. Even with limits, borrowers still carry heavy debt burdens, and repayment demands from different lenders add pressure both financially and socially.

Beyond the financial strain, many borrowers have complained of misconduct by microfinance employees. According to news investigations and victim testimonies:

Officials reportedly harass borrowers to repay on time.

Some use intimidation tactics and frequent phone calls.

Confiscation of assets to recover debts is reported in extreme cases.

These practices can lead to mental stress, social humiliation, and in tragic instances, even suicides among borrowers who feel trapped with no legal or practical escape.

While MFIs deny institutionalized abuse, individuals still report employee misconduct at local branches, which often operates with minimal oversight. This has made borrowing a frightening and emotionally taxing experience for the most vulnerable.

Many borrowers, especially in rural and remote areas, lack financial literacy — they do not fully understand loan terms, interest calculations, or repayment obligations. Without adequate counseling, borrowers sign loan agreements that may harm their long-term wellbeing.

Financial ignorance, combined with aggressive lending, creates a scenario where debt grows faster than income, and households struggle to make informed decisions about borrowing at all.

Advocates of microfinance argue that it enables financial inclusion and supports entrepreneurship. However, in Nepal’s current context, these advantages are increasingly overshadowed by the costs:

Many borrowers fail to start sustainable businesses because loans are used to cover basic needs rather than productive investment.

Loans meant for income-generating purposes are diverted to social events, health emergencies, or repayment of older debts, reducing the intended economic impact.

Average non-performing loans (bad loans) have risen sharply, indicating systemic repayment difficulties.

When debt burdens outweigh any positive outcomes, microfinance ceases to be an empowerment tool and becomes a mechanism for trapping the poor in lifelong financial stress.

Regulatory and institutional weaknesses amplify the problem:

Inadequate credit reporting makes it hard to track borrowers’ total debts.

Weak internal governance at MFIs allows aggressive targets to be set for loan officers, pushing them to lend without proper risk assessment.

Oversight is insufficient to prevent unethical behavior at the branch level.

These structural failures mean that profit motives can overshadow social responsibilities, turning institutions designed to uplift the poor into predatory lenders in practice.

To address these challenges, experts and activists have proposed several reforms:

A government taskforce recommended that all microfinance loans be insured so that if a project fails, the insurance covers repayments, easing pressure on borrowers.

Borrowers need clear legal channels to report harassment and unethical practices by loan officers or institutions.

Enhancing financial literacy before lending can help borrowers make informed decisions and prevent misuse of credit.

A centralized credit registry can help lenders assess total debt exposure and prevent irresponsible lending.

Microfinance should shift from volume-based lending to quality-focused lending that prioritizes borrowers’ actual income-generating potential and repayment capacity.

Microfinance in Nepal started with noble intentions — to bring credit to the unbanked and empower small entrepreneurs. But without strong regulations, ethical lending practices, borrower education, and proper oversight, microfinance institutions are increasingly blamed for pushing vulnerable people into debt traps that offer little real advantage. High interest rates, multiple loans, aggressive recovery tactics, and employee misconduct have turned a social tool into a source of financial hardship and social distress for many.

If Nepal is to salvage the promise of microfinance, it must ensure that borrower protection, transparency, and livelihood support become central to the sector — not mere afterthoughts.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.